RICHMOND, Va. (AP) — Dueling legislative proposals in Virginia backed by different gambling companies would open the door for an expansion of slot-like betting machines in businesses such as truck stops, restaurants and convenience stores.

At the center of the debate are “gray machines,” arcade-style games that look similar to slot machines but involve an element of skill, manufacturers say.

For years, the machines have proliferated as policymakers grapple with how to regulate them amid a big-money lobbying fight featuring stiff casino industry opposition to the devices, also known as skill games. They are currently prohibited in Virginia under a ban passed in 2020.

Now, a well-organized coalition, including one of the state’s most powerful legislators and retail owners who host the machines and share in their profits, is backing one of this year’s proposals to legalize and tax the devices. Virginia is not the only state grappling with skill games, but the efforts there reflect points in a larger debate nationwide as they have exploded in popularity.

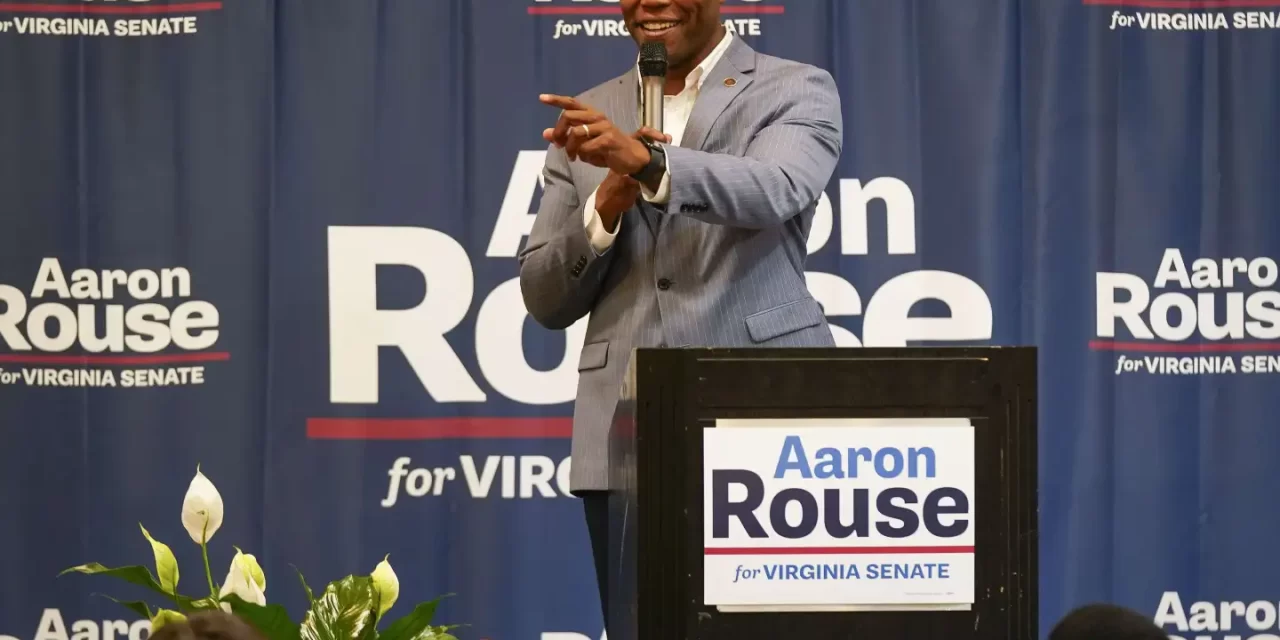

“This is a small-business issue, and one that impacts many first-generation Americans trying to achieve the American dream,” said bill sponsor Sen. Aaron Rouse, a Democrat from Virginia Beach.

The bill would set up a permanent regulatory structure in which Virginia’s ABC agency, a key revenue producer for the state, would oversee the machines. The measure includes a five-terminal limit in ABC-licensed establishments like restaurants and a 10-terminal limit in truck stops. It would tax skill games revenue at 15% and would not explicitly limit the total number of machines that could exist. Rouse has estimated the bill would create $200 million or more annually in new revenue for the state.

Only a small handful of states have fully legalized the machines in the way Virginia is contemplating, said Chris Cylke, senior vice president of government relations for the American Gaming Association, a casino industry trade group.

Supporters say that as Virginia has paved the way for new forms of gambling in recent years, including casinos and historical horse racing, it’s only fair to let small businesses share in some of the revenue.

Ahmed Makhani, who owns several convenience stores and gas stations, said that his customers love the games and that the additional foot traffic they bring creates a safer environment for his workers. In an interview, he questioned why the state would pass up the opportunity for revenue for both small businesses and core government services like schools.

Critics of the Rouse bill — notably the state’s casinos, which are also generous campaign donors — have raised a range of concerns, from reports of crime linked to the devices to worries that children will become desensitized to gambling. They also are troubled by the scale of the expansion being contemplated. While there were about 9,000 machines during a reprieve from the ban in fiscal year 2021, the bill would allow for about 91,000, critics say, based on the number of ABC-licensed establishments around the state and an assumption that each would host the maximum number.

Lawmakers are considering “certainly the largest expansion of gambling in the Commonwealth, but quite possibly, one of the largest gambling expansions in the history of the country,” Cylke said.

Some opponents also argue the measure lacks an important safeguard because it lets the industry self-report payouts.

“I don’t want the stores responsible for keeping track,” Sen. Mark Peake, a Republican from Lynchburg, said during the bill’s first committee hearing. “I want it electronically sent as dollars are going in, and I’d request that be in the bill.”

Peake noted a finding highlighted in a 2019 study conducted by the state’s legislative watchdog: When Georgia implemented an automated statewide central monitoring and audit system for its video gambling terminals, the state found revenues were nearly double what had been previously reported by the manufacturers.

The session’s competing gambling-machines bill would require that type of stricter oversight, along with third-party inspections, its sponsor, Democratic Sen. Jeremy McPike, of Prince William County, said in an interview.

His bill would not only legalize skill games, but would also open the door for video terminals McPike describes as more closely akin to slots. Both would be regulated by the Virginia Lottery Board. Profits from the machines would be taxed at 34%, with revenue projections in the hundreds of millions per year, McPike said.

McPike’s bill also would not limit the total number of machines, though it would give local governments the authority to ban them if they did so no later than Jan. 1, 2025. It would also require players to use their driver’s license or other ID to get a players’ card.

Illinois-based gaming machines operator J&J Ventures is backing McPike’s bill along with another similarly situated industry player, Accel Entertainment, said Matt Hortenstine, general counsel for J&J.

Hortenstine said his company doesn’t oppose the Rouse bill but thinks “the better policy choice is to let both devices compete on equal terms and therefore give small business the maximum choice.”

The bill, which hasn’t yet received a full hearing, is “a little stalled,” McPike acknowledged.

Rouse’s bill, meanwhile, has enjoyed special treatment, skirting a committee that typically vets gambling related-bills and instead heading straight to the finance committee Lucas chairs.

Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s spokesman, Christian Martinez, said the governor will review any legislation that comes to his desk.

The skill games debate is a rare issue that doesn’t split along partisan lines, and lawmakers have gone around and around on it for years.

A 2019 state report said Virginia, like other states, was grappling with the “rapid spread” of the machines, which at the time were not “specifically permitted or prohibited” and were not being taxed or regulated — hence the name “gray machines,” for the murky area of the law where they operated.

The General Assembly voted in 2020 to ban skill games, taking on the issue at the same time they were clearing the way for casinos for the first time.

But skill game operators got a one-year reprieve after then-Gov. Ralph Northam, a Democrat, asked lawmakers to delay the enactment of the ban by a year and instead tax the machines and use the revenue for COVID-19 relief. The ban took effect in July 2021.

A legal challenge was filed, and in December 2021, a Virginia judge issued an injunction blocking the enforcement of the ban and allowing the games to continue operating.

A bill to legalize and tax the machines died last year. In the fall, the Virginia Supreme Court vacated the lower court’s injunction, meaning the machines had to be turned off again.